Labor declares climate emergency, postpones any action til next elections

The past two months have seen a stepping up of protests demanding urgent action to tackle the climate emergency. First was the huge global Climate Strike on September 20 that saw hundreds of thousands mobilise around the country. Then came Extinction Rebellion’s (XR) Spring Rebellion, a week of coordinated actions that began on October 7 and during which disrupting business-as-usual through civil disobedience was the order of the day.

In Brisbane, protesters highlighted the threat to the climate posed by new mega coal mines, such as Adani’s Carmichael mine, in Queensland’s Galilee Basin. The state Labor government responded by demonising protesters as criminals and announcing new anti-protester laws.

Nationally, however, Labor took a different tack and sought to demonstrate that it was listening to protesters’ demands. On October 15, federal Labor announced it would back a motion put by Greens MP Adam Bandt to get the House of Representatives to declare a climate emergency — one of XR’s key demands.

Parliaments in Britain, Canada, France, Portugal, Argentina and Ireland have already done so, as has Australian Capital Territory’s parliament, South Australia’s Legislative Council and more than 60 local councils in Australia. In total, more than 1000 jurisdictions and local governments covering 287 million citizens have declared a climate emergency.

Unsurprisingly, Coalition MPs voted down the motion.

Labor’s announcement that it supports declaring a climate emergency is no doubt directly related to the growing movement for climate action. Yet it is also clear that, for now, this remains little more than an empty gesture.

Labor remains a fervent supporter for coal and gas projects that are among Australia’s main contributors to the climate emergency. Giving approval for Adani’s coal mine, as Labor has done, is incompatible with a position of acknowledging that a climate emergency exists. Clearly, if we are to have any chance of avoiding a catastrophic climate crisis, we need to start phasing coal out now rather than bring new mines online.

Labor’s national conference last December set out the policies it took to May’s federal election — an unloseable election it went on to lose.

Many Labor MPs, particularly those in seats covering mining areas, concluded from the result that the party’s climate policies needed to be watered down to regain voters. Shadow resources minister Joel Fitzgibbon went as far as to suggest that Labor’s policy of seeking a 45% reduction in emissions by 2030 should be dumped and replaced by a target more in line with the Coalition’s measly aim of 26-28%.

Fitzgibbon lost the vote in the Labor caucus room, but the reality is that even Labor’s current 45% target falls short of what is needed to reach the Paris climate agreement’s aim of limiting temperature rise to 1.5oC.

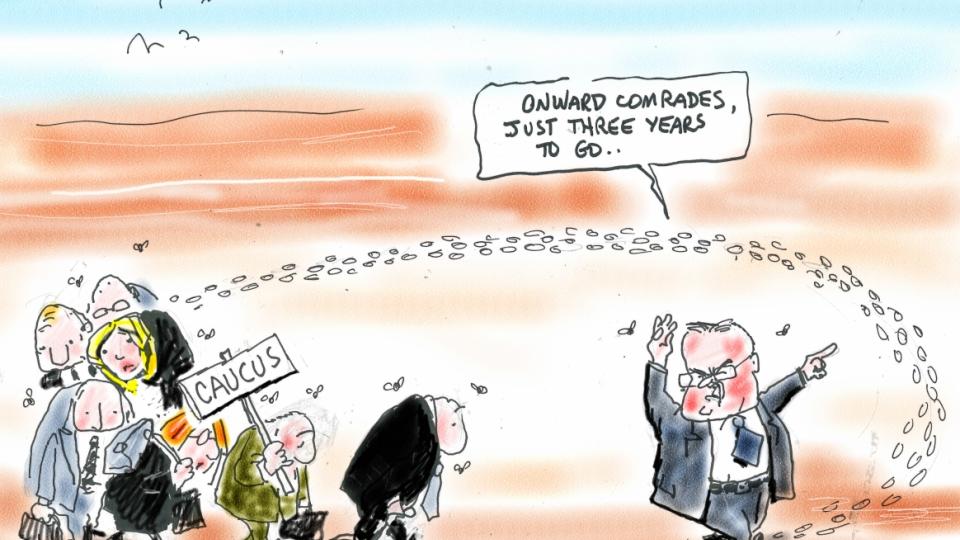

Labor has made it clear that it plans to adopt a strategy of leading from the rear. Labor leader Anthony Albanese has already flagged delaying a decision on emissions reduction targets until closer to the next election (likely in 2022) so as to avoid any confrontation with the fossil fuel lobby and sections within the party who oppose serious action on climate.

If Labor is serious about tackling the climate emergency, then it must strengthen, not water down, its climate policies — starting now.

This would require breaking out of its framework of seeking to rely on market-based solutions, such as emissions trading schemes, while refusing to phase out subsidies for fossil fuel companies that currently cost taxpayers about $11 billion a year.

It would also mean taking seriously the global impact of Australia’s fossil fuel industry, given its role as a major coal and gas exporter.

Moreover, it would require acknowledging the need for systemic change — a conclusion many in the climate movement have already come to. As long politicians continue to promote a system that prioritise profits over people and the planet, there will be no chance of seeing the kind of action needed to move us away from the brink of the abyss.

Such an outlook, however, is anathema to Labor’s pro-capitalist leadership. Getting them to even consider serious policy changes will require stepping up the kind of street mobilisations we have seen in the past two months.

Hope for tackling the climate emergency lies in the streets, not empty gesturing in parliament.